Bangladesh’s steel industry has faced a severe three-year downturn due to global and domestic disruptions including Covid-19, the Russia-Ukraine war, high inflation, and reduced development spending. Production capacity far exceeds demand, leaving mills operating well below potential. Industry leaders warn that continued investment without demand recovery could lead to consolidation and loss of competition. However, optimism remains for recovery by 2027, driven by economic stability and upcoming infrastructure projects.

Steel Sector Struggles Through Three-Year Slump, Recovery Hopes Pinned on 2027

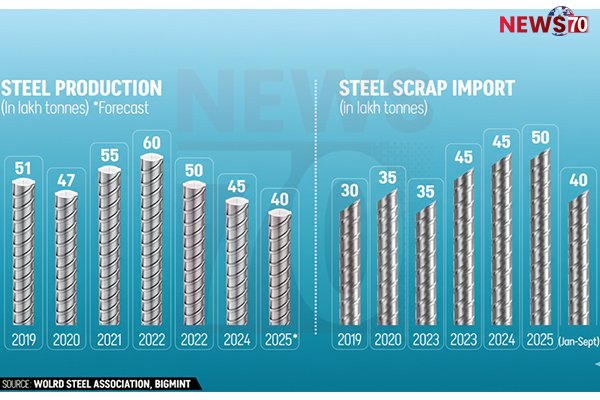

Bangladesh’s steel industry has been battered for three straight years by a mix of global and domestic crises. According to India-based market intelligence firm BigMint, demand for steel — often seen as a measure of economic strength — may need another two years to find its footing.

Industry players say the sector’s struggles mirror the broader economy. First came Covid-19, followed by the Russia-Ukraine war, which rattled global scrap supplies. At home, a weakened taka, reduced public spending, and other economic strains only deepened the slowdown.

The political transition in August last year added fresh challenges as development spending plunged. Persistent high inflation, rising interest rates, and political uncertainty have since dragged down real estate and private construction — two of the biggest steel consumers.

Today, Bangladesh’s mills can produce 1.36 crore tonnes of steel a year, but demand has shrunk to just 45 lakh tonnes, BigMint reports.

Even so, there’s some optimism. The World Bank expects GDP growth to rise from 4.8% in FY2025–26 to 6.3% in FY2026–27. “All eyes are now on the February 2026 elections,” BigMint noted, pointing to several infrastructure projects waiting to move off the drawing board.

By 2027, another 30 lakh tonnes of production capacity is expected to come online. But insiders warn that expansion without matching demand could make the market even more volatile. Crude steel output is projected to drop 11% in 2025, after a 10% fall this year.

If the slump continues, analysts say, the industry could consolidate around a few large players, squeezing out smaller mills that helped build the sector.

One of the biggest producers, Abul Khair Steel (AKS), recently opened a new plant capable of making 16 lakh tonnes of deformed bars annually, raising its total capacity to 30 lakh tonnes. That puts it ahead of BSRM, which has 24 lakh tonnes of capacity.

“The industry is limping along,” said Tapan Sengupta, Deputy Managing Director of BSRM. “Unless government spending on development projects picks up, it’ll be hard to regain momentum.”

Sumon Chowdhury, Chairman of RRM Steel and Secretary of the Bangladesh Steel Manufacturers Association (BSMA), said mills have cut production in line with slower demand and liquidity shortages. “These challenges aren’t unique to Bangladesh — many developing economies are in the same boat,” he said.

He warned that excess capacity remains a serious concern. With 1.36 crore tonnes of installed capacity and only 45 lakh tonnes of demand — down from 75 lakh tonnes during the peak of mega projects — further investment could be risky. If new projects proceed as planned, capacity might reach 1.5 crore tonnes by FY2026–27, far outpacing demand.

The association, Chowdhury added, is working with the government and banks to stabilize raw material supply, ensure financial support, and create a more predictable policy environment.

Manwar Hossain, former BSMA president and Chairman of Anwar Group, traced the current crisis back to the pandemic. “Global scrap prices jumped from $400 to $700 a tonne, but local producers couldn’t pass on those costs,” he said. “Then came the war, shipping chaos, and a depreciating taka — everything piled up.”

He said political shifts further dampened demand. “Government projects, once our biggest market, have virtually stopped. We’ve lost almost 45% of that business.”

With smaller mills shutting down, Hossain fears an oligopoly could emerge. “If only four or five players remain, competition will fade — and that’s bad for the industry’s future,” he said.